Sumerian culture is an important representation of humanity and spirituality for my research and writings because it signifies the concept of time and space; of where our ancestors made progress from in history. In ancient Sumer, the cultural elements of society were not as influenced by trade and migration as one may think; in fact, there was a uniformity of traditions that responded to social needs of those who were already enculturated.1 When evaluating the development of their written language we see progress and sophistication.

Early cuneiform texts show us an abstract pictography that required skill in reading and disseminating information.2 As Ira Spar in The Origins of Writing explains, the progress of their writing system advanced beyond an intended meaning, to a rebus principle that combined phonetic “word-signs and phonograms”, allowing scribes to better express and interpret ideas.3 The sophistication of their society is easily understood, not only because they continuously advanced their technology (much as we do today, but of course from a different starting point) but their ability to relay complex concepts are evident through myth and literature. The text, The Literature of Ancient Sumer, offers several examples of progressive thought as seen in literature – first, fables such as The heron and the turtle demonstrate how a creative product breaks convention by “bending” what appeared to be literary rules of the day; second, intertextuality is supported by the weaving of characters and specific phrases across different forms of Sumerian literature.4 In no way can we say to ourselves this ancient culture is beneath us in what we may perceive of, as status.

The artistic elements of this website are styled under a theme of Mesopotamia cuneiform writing and iconography. The fascination I have with this culture is in the intertextual nature of how concepts are formed through pictographs and share multiple meanings depending on the context of usage. Current social philosophies are challenging a patriarchal pattern of black or white, right or wrong, way of thinking. The world is becoming more aware of the spectrum of what makes humanity not different, but diverse. I have chosen to offset my research and writing with ancient symbols to provide a textual diversity to the knowledge I hope to share with my readers. An example of the intertextual use of words and images is found in the interpretation of the civilization which was called Sumer; translated as ‘great land.’ Samuel Noah Kramer in Sumerian Mythology, says of the transformative power of meaning in language:

One of the most difficult groups of concepts to identify and interpret is that represented by the Sumerian word kur. That one of its primary meanings is “mountain” is attested by the fact that the sign used for it is actually a pictograph representing a mountain. From the meaning “mountain” developed that of "foreign land,” since the mountainous countries bordering Sumer were a constant menace to its people. Kur also came to mean “land” in general; Sumer itself is described as kur-gal, “great land." But in addition the Sumerian word kur represented a cosmic concept. Thus it seems to be identical to a certain extent with the Sumerian ki-gal, “great below.” like ki-gal, therefore, it has the meaning “nether world”; indeed in such poems as “Inanna's Descent to the Nether World” and “Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Nether World,” the word regularly used for “nether world” is kur. Kur thus cosmically conceived is the empty space between the earth's crust and the primeval sea. Moreover, it is not improbable that the monstrous creature that lived at the bottom of the “great below” immediately over the primeval waters is also called Kur; if so, this monster Kur would correspond to a certain extent to the Babylonian Tiamat. In three of our “Myths of Kur,” it is one or the other of these cosmic aspects of the word kur which is involved.5

Notice how kur has a meaning that is determined by its existential impact? Kur means mountain, but it also may convey its opposite, a destination below. It resembles the idea of greatness and destination to the heavens or hell. And here is where I begin to see the connection to spirituality in its language.

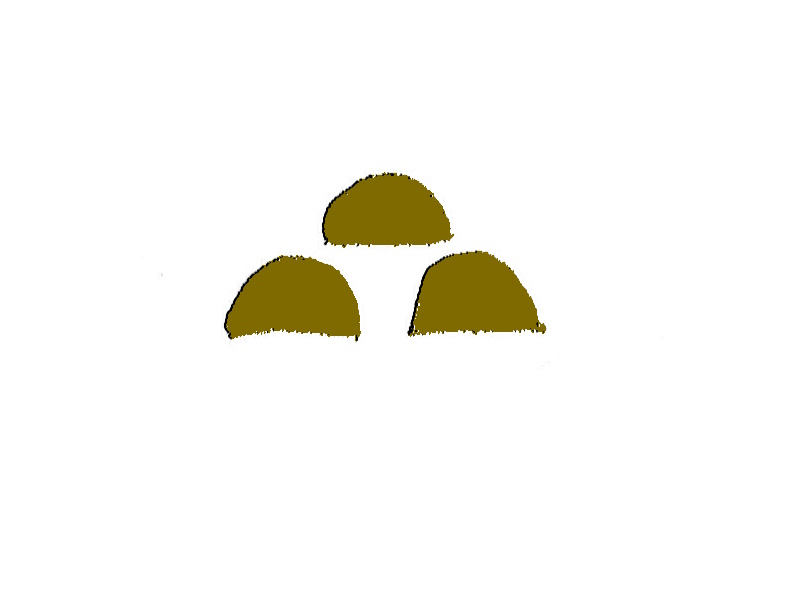

To demonstrate how this meaning is conceptualized in a variety of pictographic forms, the term kur (mountain) can be found on cuneiform tablets as wedge-shaped rounded indents, or triangular patterns, each of which use three shapes in a rising wave to look like a large, rising image6:

The term, gal (big), resembles a pitchfork with three prongs which appear to demonstrate width. 8

Ki-gal, is a Sumerian word combining the concepts of ‘place’ + ‘big’ (great Earth).10 It is not until the UR III period that logograms of combined concepts took the place of root concept pictographs.

It is also interesting to note that the concept of ‘god’ as a deity in Sumerian language begins with the term ‘decision’, or ‘to decide’. Religious aspects of Sumerian culture were a significant influence in poetry, art and in social systems where there were personal deities to support socio-economic functions. Gods ruled the social aspects of law and order for humans and expected reciprocation by the humans through rituals and sacrifice. Representation of these gods are found in the iconography of cylinder seals and boundary stones used in manners of commerce and traditional practices.12 The word for ‘god’ as a divine being is called diñir, where di refers to ‘decision’ + ñar refers ‘to deliver.’13

Gal-di means ‘mighty judge’ which is a both an adjective the god Enlil (who is the god of storms) and made from the combination of ‘large’ + ‘to decide, judge.’15

There are two aspects to these pictographs. First, the symbol for gal-di is eight-pronged, while the symbol for ‘di’ has four sides. We know numerology and mathematics were prominent in Sumerian culture, considering we still use their methods for calculating time. On the website titled, Temple of the Seven Spheres, Sumerian numerology is explained as that which is mathematically divisible by 60, the number’s planetary associations, and their relationship to the gods:

8 has no perfect reciprocal to 60 but due to its imbalance to 60, it is the number of Conflict and Obstacles that must be overcome. It is also the number of Nergal the Lord of the Underworld(mars) and has the reciprocal of 45 to 360. 8 are the rays of the star that means ‘god’ in cuneiform and all the gods but Enki and Anu went to the realm of death to face trials and obstacles in order to learn a moral / social lesson.17

One of the more familiar Sumerian symbols from the UR III period is the logogram for ‘god,’ which brings together the numerological associations of four and eight. Here, we see the eight-pronged symbol of gal-di, with four of its points in the north-western direction tipped with triangles. The number four represents the four elements of Earth, Air, Fire, and Water. Just as the term kur means mountain as well as the underworld, with symbols that reach to their heights, the term digir (opposite to kir, or place/Earth) means ‘sky’ and contextually the general description for god. The gal-di must go through the underworld, to make a decision of going through the obstacles of death to reach the heights of morality.

Please remember I am not an expert in this field of study, I am simply explaining the insight I have gained so far as I have studied and relating it to the information I present through my writing. When I really look at the cuneiform tablet included above, and the pictographs embossed in it, I see transactions and relationships. I see complex and sophisticated methods for a society to go along with their lives and reach their personal goals. I see a society not unlike ours and being the oldest known form of writing and one of the oldest civilizations on our planet, there is a sense that our roots are trying to reveal to us a truth about humanity. Even across time and space, in fact, regardless of time and space, we exist as one humanity. There are lessons to be learned from our ancestors. Our fates our intertwined. In a poem I wrote about the story of Atrahasis called The Epic Flood of 2020, as a reflection of how to overcome the trials of the flood, I consider the relationship between Ancient Sumer, and all the ways we have been part of a great ‘flood’ which has brought devastation to the people. It is through the myth of Atrahasis that I found one possible answer to human strife: to create a drum that beats together, to say ‘Yes’ to life and to work through life’s challenges together, with one voice.

Footnotes:

- Jacobsen, Thorkild, “Mesopotamian Religion: Cult,” Encyclopedia Britannica, June 13, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mesopotamian-religion.

- Spar, Ira, “The Origins of Writing,” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/wrtg/hd_wrtg.htm

- Spar, The Origins of Writing, 2004

- Jeremy Black, Graham Cunningham, Eleanor Robson, and Gábor Zólyomi, The Literature of Ancient Sumer (New York: Oxford University Press Inc., 2004), xxiv-x.

- Samuel Noah Kramer, Sumerian Mythology: a Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millenium B.C., Rev. ed. (New York: Harper, 1961), 76.

- John A. Halloran, “Sumerian Lexicon: Version 3.0,” Sumerian Language Page, November 5, 2021, https://www.sumerian.org, 106. This source provides an accessible translation of Sumerian language. Often a logogram, a combination of two or more concepts, will be described by breaking down the pairing of concepts to understand how the elements combined create a full Sumerian word. For example, if I search the document for the English word mountain, I find ten matches. One of the matches is: “kur-gal: great mountain – a metaphor for temples and for Sumer as a place where Earth and Sky meet (‘mountain’ + ’big’).” Knowing the Sumerian word has helped me to find the corresponding pictograph in the source written by Ashur Cherry (see note 7 below).

- Ashur Cherry, Archaic Sumerian Pictographic Signs (Toronto, Ontario: York University, 2016), Accessed: June 18, 2024, https://archive.org/details/AshurCherryArchaicSumerianPictographicSigns/page/n1/mode/2up, 46. The pictographs provided in this source are estimated to be from the time period of 3500-3000 B.C. These pictographs are like the etymology of a word, which is like breaking down the word to its various, originating parts. Each part of a word has its own pictograph. The combination of words (as described by Ira Spar in The Origins of Writing, see note 2 above) were developed in a later period, which means new logographs (produced by combining these word-parts) were also created.

- Halloran, Sumerian Lexicon, 85. See note 6 above.

- Cherry, Archaic Sumerian Pictograph Signs, 21. See note 7 above.

- Halloran, Sumerian Lexicon, 102. See note 6 above.

- Cherry, Archaic Sumerian Pictograph Signs, 43. See note 7 above.

- See note 1 above.

- Halloran, Sumerian Lexicon, 77. See note 6 above.

- Cherry, Archaic Sumerian Pictograph Signs, 13. See note 7 above.

- Halloran, Sumerian Lexicon, 85. See note 6 above.

- Cherry, Archaic Sumerian Pictograph Signs, 5. See note 7 above. This was much more difficult to figure out as dinir is the compound word for god. We find dinir as a pictograph symbol under the word for An, which we learn is the name for the god of the heavens (Halloran, Sumerian Lexicon, 6).

- “Concerning the Numbers of the Gods,” The Temple of the Seven Spheres, Accessed: June 18, 2024, https://dulakaba.tripod.com/id70.html

- Sjur Cappelen Papazian, “The Sumerian pantheon: An, Dingir, Nin/Eresh, Shar,” Cradle of Civilization, July 28, 2015, https://aratta.wordpress.com/2015/07/28/the-sumerian-pantheon-an-dingir-nineresh/

Leave a comment